Lately, I’ve been in this weird mindspace where I keep wanting to revisit Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me. Not just casually either, I mean literally right after watching it I want to run it back again. David Lynch’s misunderstood masterpiece from 1992 is not exactly a great hang: completely eschewing the more quirky, sillier aspects that fans loved about the Twin Peaks television series in order to relive the final days of Laura Palmer, the dead beauty queen at the center of the show’s darker mysteries. Certainly #A #Choice by Lynch at the height of his power, one that has been written and talked about endlessly, that goes a long way to explain the absolute animus the film received upon arrival.

Nothing validates great art like time though, and now Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me is seen as absolutely vital—to the Twin Peaks canon and to David Lynch’s filmography. Arguably the true essence of Lynch’s vision for the series and easily my favorite film of his. A movie I keep wanting to return to for a number of reasons, but maybe most importantly because the vibes are so immaculate.

I am not particularly good with keeping up on pop cultural anniversaries, which makes being a culture writer in 2022 next to impossible. Regardless, I could not let this year end without talking about this movie. From a technical standpoint, FWWM is an achievement in atmospheric filmmaking. Its dreamlike surreality and mood establishing jazz by longtime Lynch composer Angelo Badalamenti shifts between tranquility and discomfiting uneasiness in smooth fashion. It’s Lynch’s most beautifully shot film, with several scenes that are good enough to be paintings. It’s a gorgeous bath of light and sound design that needs to wash over you completely to be its most effective. Everything is a little bit off, rougher, scarier, more gruesome than could ever have been allowed on primetime ABC.

The film essentially has two parts (if not quite halves), the first follows FBI director Gordon Cole (Lynch) leading an investigation into the murder of Teresa Banks. The detectives sent to Deer Meadow to look into what is referred to as a “Blue Rose” case (strange/ supernatural happenings) are Chester Desmond (Chris Isaak) and forensics expert Sam Stanley (Kiefer Sutherland). Deer Meadow is presented as the anti-Twin Peaks: instead of folksy, happy-go-lucky sheriffs and diner waitresses, the people are abrasive and down-trodden. Lynch is known for taking that glamorous 1950s white American vision of itself and exploring the deep soul rot within, but here in Deer Meadow is almost an attempt to contend with America as it is, where the rot is evident, systemic. Teresa Banks was another woman that, like Laura Palmer, was doomed from the start, with no home or protector to save her from the evil around her. The Deer Meadow investigation is mostly amusing when it’s not harrowing and nightmarish, like the scene of Teresa’s autopsy. It’s full of strange moments like the Sheriff’s office scene and the infamous “her name is Lil” scene that all but laughs at the people who obsess over deciphering Lynch’s work. Most notably, this is the part of the movie that features the bulk of Kyle MacLachlan. Special Agent Dale Cooper infamously ends Twin Peaks trapped in Lynchian dream purgatory and ends up not mattering much at all to this film, though that’s partially a result of MacLachlin’s disinterest in returning to the world soon after the series’ cancellation. Regardless, despite not being in much of it, he at least gets to be part of one of its very best scenes, alongside Lynch, Miguel Ferrar’s Albert Rosenfield, and David Bowie as the long-lost agent Philip Jeffries.

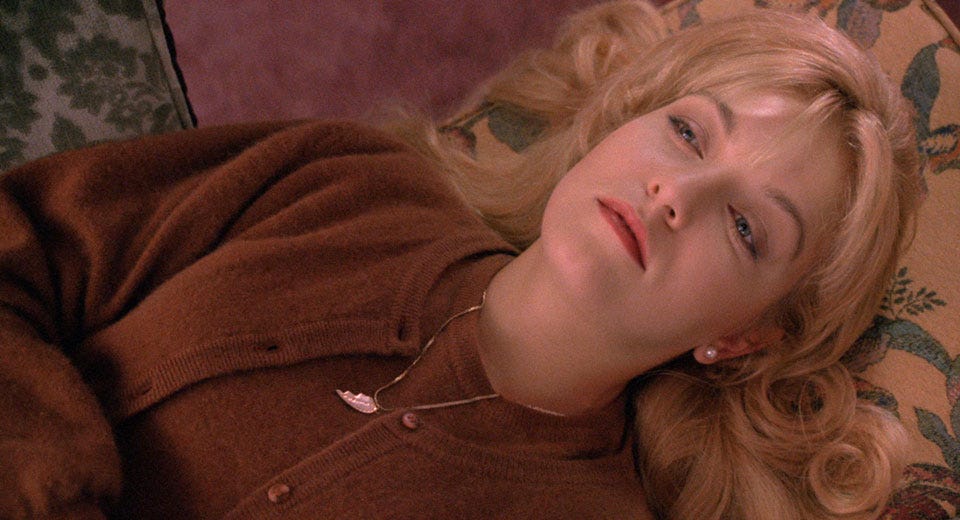

The rest of the film concerns that last week in Laura Palmer’s young, tortured life. Sheryl Lee is a magnetic, harrowing force; a true revelation that carries the film and effectively channels the pain and suffering that Laura feels. Lynch gets a lot of flack for his depictions of violence (particularly sexual violence) against women. The line between depiction and exploitation can be thin and thorny and it’s not my place to argue that any viewpoints for the latter are wrong, but it seems pretty clear that at the very least Lynch is deeply empathetic to the women of his stories, none moreso than Laura who has her agency returned to her in this film. She is hypnotic and dangerous, as much as she is traumatized and suffering, walking about town in a haze of drugs and cigarette smoke. No one is coming to save her and she knows it, so she holds onto her dignity in death.

The infamous pink room scene where Donna (Moira Kelly) follows Laura to one of her sex work jobs is intense and bizarre, bathed in red light and strobes and screeching guitars. It can feel like a cross between softcore porn, MTV, and a nightmare of exploitation, but it’s also where we see Laura’s true affection for the people in her life. Her desperation to keep Donna away from the darker aspects of her own life and preserve her innocence is moving. The painful reality in FWWM is watching the way Laura circles the drain with no one in her life capable of saving her, even if they could understand anything about BOB or what’s happening inside her home. She is trapped in a hell made literal and coping by any means available to her.

One of the weaker episodes of the Twin Peaks television series is season 2’s “Arbitrary Law,” aka the episode where Cooper solves the mystery. It comes after Lynch all but quit the show after being forced by ABC to answer the question of who killed Laura and it is an hour of mostly overexplanation about the show’s lore. Some of it works, like the endnote where Cooper, Sheriff Truman, Albert and Major Briggs have a powwow about the mysteries of the universe, but most of it feels like trying to hold the audiences hand about what the show is. But the worst crime in that episode is the way the show absolves Leland Palmer of all guilt and agency in the murder and rape of his own daughter. Leland, as he’s dying, gives an impassioned speech about how BOB came to him when he was a boy at his family’s lakehouse and that he had no control over his actions when BOB took over. Although by the letter of the law, you could say that’s true—the point of BOB is he is the evil actions of men personified—and while there’s plenty here to discuss about generational cycles of abuse, robbing Leland of his agency and making him out to be “a good man” that just so happened to have an evil spirit take over his body from time to time, does not keep in spirit with what Lynch was trying to do with this story. And if you don’t believe me, just watch the Leland of FWWM for yourself. Leland is ultimately a man who loved his daughter and was a victim of BOB but he was also a willing vessel of that evil, as evidenced in the Teresa Banks storyline. Part of Lynch’s desire to not answer the mystery of who killed Laura was because everyone had blood on their hands. Twin Peaks let Laura down the way America always lets women down, and while I do think the show is better with that question answered, I get his point. Smarter writers than me have pointed out the similarities between Laura Palmer and Marilyn Monroe, but really she could stand in for so many abused and tortured women throughout history, because it is a cycle that continues to repeat itself.

FWWM submerges you into the nightmare but the hope of some otherworldly magic coming for Laura’s salvation is always there at the margins, often in the form of actual angels. You know she is doomed but the movie wants so much for her that it stretches past the bounds of life and death. Watching Blonde, a movie that thinks it is doing Fire Walk With Me at many intervals, what I found most reprehensible about it was just how deeply uncaring it is towards Marilyn, as opposed to FWWM which has so much empathy. And it is that empathy that has allowed people to come around to the movie’s wavelength over time.

If you want to send any questions, comments, concerns, good vibes or hate, or advice, email me at iodaramola@gmail.com. Thanks for reading. The newsletter is free but you can show your appreciation by donating whatever you can to the fund here. (or CashApp $iodara).